When Nicole Johnson was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at 19 years old, she “spiraled into hopelessness”. Flipping pain to purpose, Nicole volunteered, became Miss America, and obtained a Doctor of Public Health degree.

Before she became the first Miss America to publicly use an insulin pump, Nicole Johnson, DrPH, was a 19-year-old English student at the University of South Florida with the world at her feet. When diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, Nicole’s health care provider presented a negative forecast for her future.

Aside from physical symptoms like fluctuating blood sugar levels, Nicole felt alone—even amongst her family. It was hard not to notice the different place in the house where her food was kept and different preparation routines for only her meals.

Having to manage a chronic disease during this vulnerable life stage caused Nicole to “spiral into hopelessness” and she dropped out of school. Learning to live in the ambiguity of life with diabetes made Nicole angry, and “it felt like everything was being ripped away” from her. In hindsight, Nicole can appreciate the anger because it helped her move forward, a point that not everyone reaches.

“With diabetes, we learn to cope, but we don’t get resolve.”

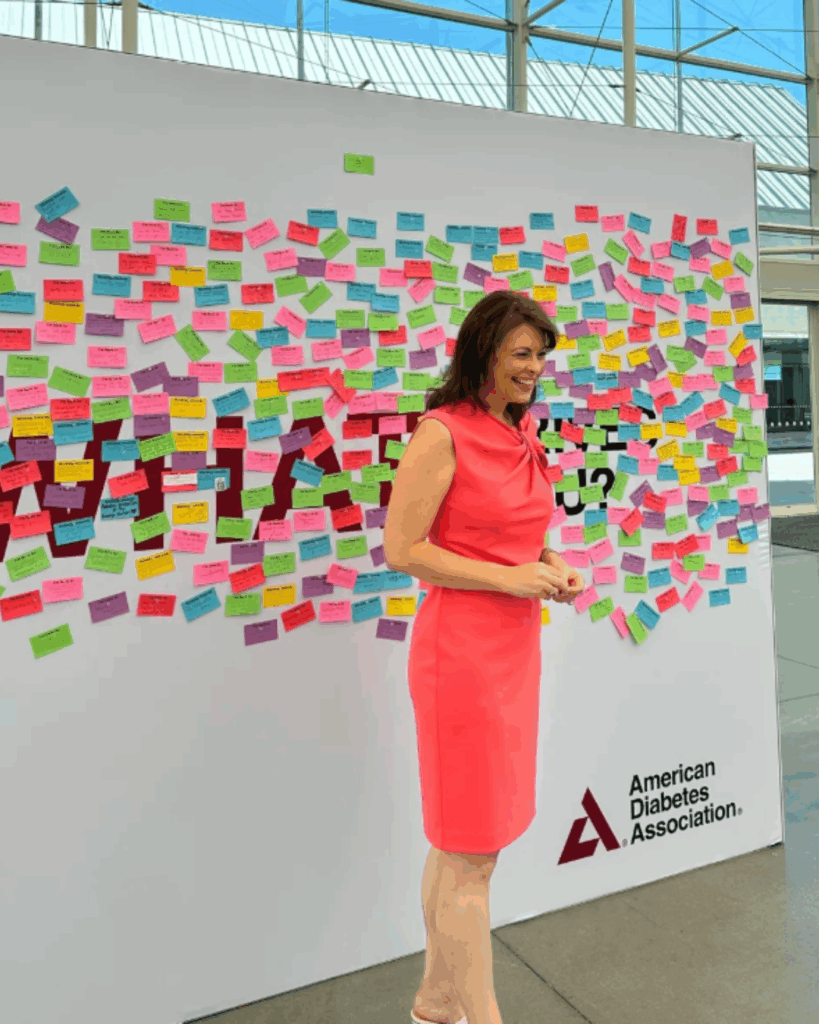

One week post-diagnosis, Nicole was discharged from the hospital and went to a Breakthrough T1D office (then referred to as JDRF) to volunteer. Motivated by her desire to advocate for other people with diabetes, she also became a spokesperson for the American Diabetes Association and discovered pageants, winning the titles of Miss Virginia 1998 and Miss America 1999. Both times, Nicole sported an insulin pump and became the first contestant to do so.

“On the surface, you’d think I was into pageants. But I wanted to use my involvements to prove people wrong—those that said you can’t do all these things,” Nicole said.

It was during this time that Nicole met Dr. S. Robert Levine and Mary Tyler Moore at a JDRF Gala. “I was able to talk with someone who had first-hand experience of the vision issues, including vision loss, you can have from diabetes. Diabetic retinal disease is one of the scariest parts of diabetes,” she said. “But Mary showed me that despite the challenges, you can serve the greater good. She was such an iconic figure to me as a young woman.”

Advancing her advocacy work, Nicole went back to the University of South Florida for a Doctor of Public Health degree and later created a university program called Bringing Science Home, which helps young people with the transition of caring for their diabetes more independently—a full-circle moment.

Today, Nicole’s life looks a bit different—she’s the Community Education and Screening Education Manager at Sanofi and the mother of a college-aged daughter—but that hasn’t stopped her from staying actively involved with Breakthrough T1D and the American Diabetes Association.

“My daughter doesn’t have diabetes, but she’s the age I was when I was diagnosed. Now, my commitment to diabetes screening and research is no longer about myself, but her.”

“So much progress has been made thanks to organizations like The Mary Tyler Moore Vision Initiative. My wish is that science continues advancing so people with diabetes are given hope that the burdens known to previous generations will not be their reality.”